The second in a continuing series (Click the ‘Tales From Topside’ category heading above to see the rest). Doug Podgorny was area manager ovens up until the very end. With 25 years between the coke plant and mill, he watched things start to unravel but had to stick around to see it through. Never before has this story been told, first hand. Stick around for more.

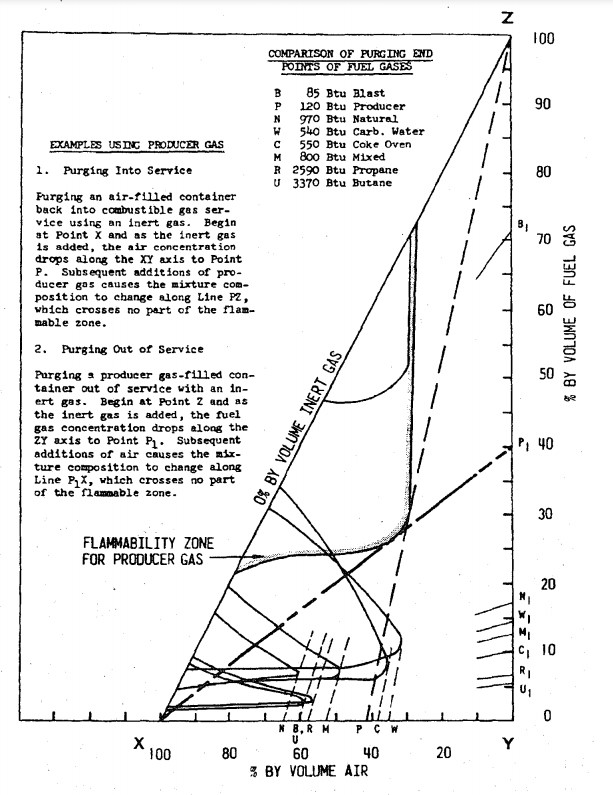

So it had come to this. The first concrete sign there was big trouble on the horizon. Plant wide, each area had a plan to “purge” their area. Although piecemealed to maintain structural integrity, the plant would occasionally have an issue that needed fixed fast, and many occasions to do things that would prevent those “fast fixes”. So every operating area had a plan and all had been exercised many times – we just never did the whole plant at the same time. Logistics of lining up resources to facilitate a safe purge as well as coordinate the efforts of operations and maintenance to sequentially perform orchestrated actions were huge. After many meetings we hashed out a plan we all agreed was best. “What could go wrong?”, as Murphy would say.

In my years there and I lived thru many operational outages scheduled and unscheduled. I can proudly say that never did anything resembling an uncontrolled explosive event take place. Maybe several “pops” in the basement due to the misalignment of a reversing core, or a small external main fire because somebody on the battery said “I thought Frank was gonna get that seal”. But every purge is executed in a manner that eliminates those, and when it doesn’t, we modify the plan.

Coke oven gas only has about 25% of the BTU value of propane but it can still blow up pretty good. It burns like a super heated blow torch under pressure when there is enough air to support combustion. Get the right gas/air mixture isolated in any section of pipe/vessel and add a haphazard spark and you have the potential explosive impact of a loosely packed pipe bomb. Big enough to maim and kill plant personnel with local heavy damage. The light oil recovery plant was a little different. In almost all of the gas recovery system the hot coke oven gas is sprayed with “flushing liquor”, a mixture of mostly water but some tar and residual hydrocarbons. And it did not burn well, so it got shut off in a purge meaning you had to work fast to push the COG thru with an inert gas (nitrogen was preferred). Light oil was recovered by super steam heating a “wash oil” and capturing the concentrated benzine, xylene and toluene via a still. Several well know carcinogenics and quite explosive as well. Big explosions, like rocket fuel explosions – think of the Challenger, but on the ground.

So – professionally as always – we planned. And we mostly managed to professionally deliver our best. Morale was not good, but we knew if we got a chance we knew we could be a money maker in a year or so. I will admit it was hard for me to maintain a sense of humor and I began to take long and hard looks at reality.

The coke plant was never an easy place to work.. You had to be a certain sort of guy to survive there, even on a day where everything went like clockwork. Depending on which direction you traveled and which way the wind was blowing you would begin to sense the plant at about a city block or two away. If you know what burning coal smells like you would recognize it immediately. As you drove into the plant, many times you would be treated to the pungently sweet smell of jet fuel. Soon you would be able to experience the smells associated with being stuck in a traffic jam next to a tarring crew on their lunch break. And if the still wasn’t working properly, expect a nice shot of ammonia.

You never wanted to lose sight of your situational awareness at any time. Lots of things there can kill you quick if you fail to pay attention. Unfortunately, a few of us didn’t. And the noise! Sirens, alarms and whistles for everything. Movement alarms on everything that moved! Heavy equipment and machines always running. Walkie talkies for everybody, even a plant wide loudspeaker to add to the gulag motif. Not to mention the weather! Chicago winters should have merited everyone an extra six months pay. It took that much more effort in the winter.

But there’s the rub. Simply put, the place paid pretty well. Not rich well, but certainly enough to maintain a comfortable life. A house, two cars and two vacations a year comfortable. Most coke plant guys didn’t have much more than high school and heavy industry exposure. When I started my initial salary was equal to the American median income level for that year. Not a bad start for a new college guy in a tough economy. An hourly guy with 16 hours of overtime could match that – not a bad living. Steel was in trouble because the economy was in trouble . “Gonna be hard to replace that income” was on everybodies mind. Bills to pay, kids and cars and pets to feed…but we pressed on, still having a reasonable doubt.

And then the news came.