Bob Green (clock# 253) reached out to me after finding my website and we had a great back and forth via email, which is posted here. Bob has other contributions in the pipeline, and we also plan to visit the plant together soon and document that via video. Stay tuned!

Bob, thanks so much for taking the time to chat. What was your career at Acme/Interlake like?

At the coke plant, I was a laborer in coal handling, janitor, wharf feeder, conveyorman at the wharf and heater helper. I started at the coke plant in coal handling back in January 1978. Two months later, I won a bid to move over to the ore dock at the furnace plant. I was brought back from lay-off to the coke plant in 1984, working as a door cleaner on the ovens. After another lay-off, I was brought back as a janitor in 1987. I got moved to the wharf, feeding the #4 conveyor belt. In 1988, I got sent to the ovens as a lidman and door cleaner. In the fall, I moved to conveyorman on the wharf. Then on to heater helper. Worked there from 1989-92. I wasn’t that far away from moving up to heater when I moved to the furnace side in 1992.

Have you visited the plant since the closure in 2001?

I have visited the plant in 2016, 2017 and 2018. In 2018, I was checking out Big Marsh. While I was there, I took a walking trail which led me to the railroad tracks and the plant on the other side. I gave in to temptation and went in, but I didn’t go too far in that time.

My friend, Eddie Contreras went with me 2016 and 2017. He ran the larry car before going to the furnace plant. I worked with Eddie, his brother, and his father on the furnace side. We got another friend, Rose Norman, to go with us in 2017. Her 25 years at Interlake/Acme was just about all at the coke plant. She worked with me on the wharf. Rose’s grandfather, father, sister and uncles all worked at Interlake/Acme. I worked with one of her uncles.

What was it like working on the wharf?

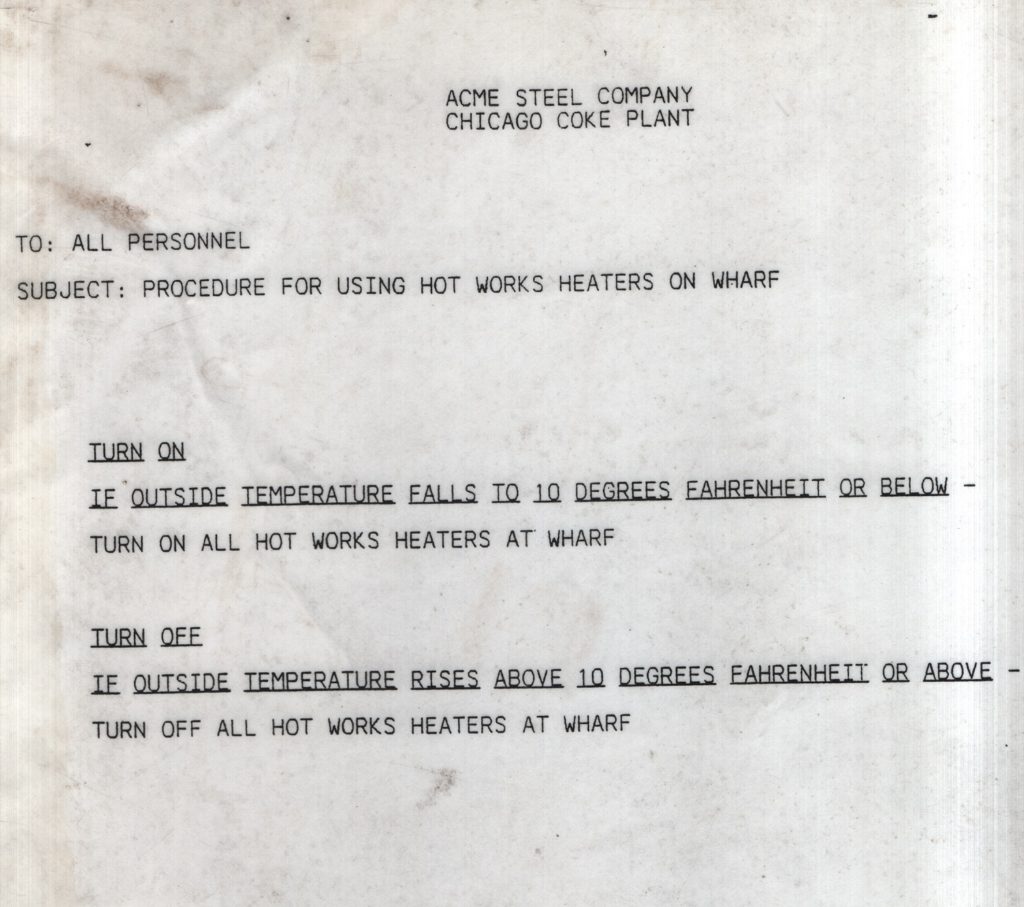

#4 belt never broke on me, but when the belt stopped, we would communicate with the screening station at the furnace plant. If it was going to be down for a time we would stock the coke in the yard near the wharf. One time, it was down for a couple days and they trucked it over. I often had a bad quench car operator. He’d catch the push on one side of his basket instead of spreading it, so it didn’t get put out. Sometimes, I would have to break out the fire hose to put out the flaming coke. One time, it was -50F wind chill. I had the fire hose out and by the time my shift was over, the wall and ceiling over the walkway had a coat of ice on it. It looked like an arctic cavern.

Working topside as a heater helper must have been much different than being on the wharf.

As heater helper, I worked with the heater. We would go topside, looking down gas flues of the walls and taking temperatures. I had to watch over the collector main. It collects gas from cooking the coal, where it went to the BP plant. They cleaned up the gas and sent it back to us to burn in the flues of the walls via the under firing system in the basement of the batteries. We cleaned and maintained that system. We had a control room at ground level, in the coal bin building, east side.

Besides being on top of the battery, you had other responsibilities below it as well, right?

We used to clean pins (metering pins), swapping cocks (reversing cocks) when the inner or outer zone were off (gas) in the basement. When the BP plant loses suction on the collector main, the ovens would build pressure, and we would have to open the bleeders (flares) on top and burn off the gas. Turned night into day. Once, the collector main lost it’s liquor (coolant), I had to open the valves for mill water then run down to the control room and turn on the main valves to cool the collector main.

There was lots of piping in the basement – the pipe wrench was our main tool down there. Most of the time we used it when we swap cocks. There was piping underneath the reversing cocks, coming from the gas main. We shut off the gas, take off the pipe plug at the bottom of vertical pipe leading to the cock. We had a big pipe brush welded on a 4 or 5 foot cable. We’d run the brush up and clean out carbon in the reversing cock port. Put the plug back on, then wait on the reverse and repeat to clean the other port. When I first started in the heating dept, we took apart every cock on both batteries, cleaned and regreased. We used grease to seal the cocks. Sometimes add pump of grease every so often. Once we lost power on the ovens and had to turn the reversing machines by hand. With the under firing system, we heated the outer (zone) part of the wall for 20 minutes, then the inner zone of the wall for 20 minutes. The reversing machine in the control room would move the arms of reversing cocks (valves) in the basement. With the power out, we had to turn a big wheel manually in each battery. Turning by hand is hard – luckily, we got power back in 20-30 minutes. I think there was a battery back up, but that failed that evening.

When we cleaned pins (metering pins), we’d lock out the reversing machine, go downstairs, shut the gas at the main, and work in the off zone. The helper would unscrew and clean the pin, then set on top of the orifice. The heater would follow, brush the orifice, and screw the pin back in. 15 pins on the inner zone, 14 pins on the outers, per wall. We do five walls at a time. Each crew had to do five walls per shift. Me and Danny Hunt had the ‘C’ section on battery #2. Willie Gilliam had the B’s. Frank Greco and Gerry Bowden had the other sections.

Can you explain a little more about the designations for walls and ovens?

‘B’ section was B-1 thru B25e, the south half of battery #1. In the basement, we went by walls, not ovens. Each oven shares a wall with the oven next to it. There were two end walls on each battery. On #1 battery, the end walls were A-1 and B25e. The ‘e’ stands for end. Upstairs in production, the ovens were numbered B-1 thru B-25, but in the basement we were concerned with the walls.

Did you ever get up to the top of the coal bunker?

It’s been over 40 years since I been on top of the charging bins – those stairs are steep. Going up there, I used the C21 and C22 conveyor belt and it’s housing. What I love about being up there is the view of downtown, my old neighborhood, a mile to the north, and all around. I used to like climbing to high places in the mill for the view.

Another point of high elevation at the plant was the #4 conveyor over the Calumet River. I’m guessing you got to walk up there a few times.

Been on the coke belt bridge many times. Even climbed outside of the enclosure over the river. It was the only suspension bridge in Chicago. A couple times, I was up there, over the river, at dawn. I had a view of Wisconsin Steel on one side and a view overlooking Republic Steel, the Whiting Refinery, and Inland, J&L Steel behind it. I would think of the history of this region, going all the way back to the turn of the century. When The Blues Brothers came out, it had a scene at the beginning, of the refinery and Southworks. I said to myself, “I’ve seen this before”. I was thinking about the workers that came before me. The steel industry heyday was over in Chicago by 1980. Acme had the last working blast furnace in Chicago from the 1980’s till closing at the end of 2001. We weren’t in the news much on the decline. But the Chicago steel mills at the time built downtown.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up on the SE Chicago. My mother use to take me to the 95th St bridge to watch the ships. Many of them being ore boats. I ended up working on the ore boats when I was on Interlake’s ore dock. When I was in day camp as a kid, my school bus would pass by Wisconsin Steel’s BOF. Loved when they were poured hot metal. Then passed the coke plant and held our noses. It really stunk. It was the BP plant that stunk – this was before the clean air act. Wisconsin Steel use to dump slag pots at night and would turn the night sky orange around the southeast side. I lived a little more than a mile away. It was something to see. They dumped about a block north of 106th St, about a block east of Torrence. That neighborhood became known as Slag Valley. Slag pits are dangerous. Thing is, sometimes there’s a little iron that gets poured along with the slag. It’s the iron on top of water that is bad news. Our blast furnaces poured the slag outside the casthouse into one of two slag pits. Every once in a while, they would blow. Once it blew on the shift before mine, while the train crew was down there. Nobody got hurt, but it left boulders off the deck of the locomotive engine. Another time, our train was coming down the highline, and ‘B’ furnace pit blew. We were still far enough away, but I watch as Suzy, who was working on the highline by ‘B’, run and seek shelter under the coke hopper, as flaming slag and boulders were flying through the air. A lot of times, there was a tractor driver cleaning one pit while pouring slag in the other pit. No, I wouldn’t want that job.

What have you been doing since the coke plant closed?

When Acme closed, it threw us all for a loop. Some never recovered. We lost a lot of coworkers. Some of died of cancer. When I brought Rose to the wharf area in 2017, there were tears in her eyes. She spent most of her life there. I worked for Caterpillar for 10 years. I was a steelworker for 24 years and an autoworker for 10. I rejoined the USW when I retired, their SOAR (Steelworkers Organization of Active Retirees) chapter. We meet at the old Republic Steel union hall at 115th and Ave O. We are organizing our annual commemoration of the 1937 Memorial Day Massacre. It’s on May 21 at the union hall. So far, we got the VP of the AFL-CIO speaking at the commemoration. There is a memorial statue by the fire station at 115th and Ave O. It was moved there after Republic Steel closed in 2002 for safe keeping.