After locating a training tape in the main office last weekend, a brief bit of internet research led me to the owner of the voice I intently listened to through my speakers. Jerry was glad to have a discussion about his memories of the coke plant via Zoom. I used the transcript of the audio recording of our 90 minutes conversation for the below Q&A.

My knowledge is that they stopped using the Interlake name around 1986. So I figured that tape has got to be at least that old. But you’re saying you think maybe 10 years before that.

Yeah, it definitely was. Because, wow…I started the business right out of college and that was 1974. I got married in 1978. We incorporated and changed the company name from ‘Jerry Feil Productions’ to ‘Feil Productions Incorporated’ in 1979. So the tape that you found was Jerry Feil Productions. So before I was married, basically…it had to be before 1978.

Well, that’s awesome that you were able to figure that out based on your company name at the time. One of the first things I wanted to ask you was who did you find with the golden voice to actually do the voice over and you told me “No, it’s not just my company. That was me doing the voiceover”

Yeah, that was me. I started doing training programs because I was an engineer by degree and interested in teaching. So I did training programs for companies in the Chicago area. Right out of college, kind of started a business in the bedroom at my parents house in Oak Lawn. Interlake was a customer, Commonwealth Edison was a customer, and a few others back in the really early days.

Was the slides with the audio on a cassette kind of a standard training program that you did a lot?

If you think about it, that’s really before video. I mean, a video recorder was thousands of dollars in the seventies. So a standard kind of medium for training programs in companies was a Kodak carousel of slides and a cassette tape. The projector was like a box with a little built in rear screen.

And besides doing the voice over, you did all the photography for the slides.

I mean, I had my Nikon camera, I was out there in the coke battery with the heavy shoes and the respirator and took my pictures up there. And it was kind of a weird thing because I was the engineer kid from the suburbs. And at the coke plant it’s a whole social thing. It’s kind of a dirty job.

Yeah, sure. You’re a little bit of a fish out of water. It’s a rough bunch up there.

Perhaps I’m worried about my camera because it was the most expensive thing I owned at the time. And here I am in this nightmarish environment with smoke and machinery but it was kind of interesting.

The voice over copy gives an excellent description, like someone who’s been around it for a long time. So whatever resource you had to contribute to that script…well done.

That’s my understanding of how pushing works. I spent a fair amount of time there, not like full time or anything, but over a several year period did a number of training programs. Started off with some basic safety practice stuff about shoveling around conveyors and things like that, you know, just to minimize accidents. Sometimes new people weren’t familiar with working around heavy equipment. So some training programs, safety training and then, to a certain extent, environmental. But I spent a fair amount of time in the plant walking around. I even walked, I think it was called the number two conveyor that went from the coke plant to the furnace plant.

That is number four. Did you have a logistical reason to take this walk? Or is he just like, hey, check this out?

I was with my guy from corporate, the training director. Just to explore. There is a catwalk next to it. The whole thing was covered and a lot of times you were walking along and you really didn’t know where you were until you came to an opening and you could look out.

And you’ll be over the river or over above Torrence Avenue. Can’t even imagine. That’s phenomenal. Where was your first project? At the coke plant, or I know you said you did some programs for the furnace plant as well.

The very first program was at the coke plant, that was kind of a general safety orientation. Just wear your hard hat, wear your safety shoes and your respirator and typical kind of stuff, just being around moving equipment. Because there are door machines and pushers and larry cars, all heavy equipment. There’s a lot of opportunity for you not to pay attention and get whacked by a piece of equipment that’s coming by unexpected. Even shoveling around conveyors. You could get your shovel caught in the conveyor under the belt, and if you don’t let go, you could be pulled in. I did some other programs. There’s the pusher, one that you mentioned, and then I know we did stuff for the quench car operators and the larry car.

Oh, my goodness. Yeah, There’s quite a few more tapes out there somewhere.

And then lesser things at the furnace plant. I didn’t do a lot. Maybe just one or two programs over there and maybe the same for the plant over on Perry.

You know, I got this tape home and cross my fingers and hit play. And as you could hear, the audio is absolutely pristine. I have tapes that have never left the inside of my home that are of similar age. They sound awful, they’re full of drop outs. You must have bought some high quality tape. The magnetic medium itself has lost nothing. It never drops out, it played perfectly. Just the frequency response…I couldn’t couldn’t believe it.

See, there you go. Customer testimony. Well, it’s funny, because when I was in school for engineering, my part time job was selling stereo equipment for a chain called Playback, back in the seventies. And so I knew a lot about audio equipment and recording and all that stuff. So I was really into audio engineering kind of stuff. And I was a geek in terms of broadcasting, not in terms of on air stuff for music, but the transmitters and the recording equipment. I was really into all that.

You know, a hell of a lot about a coke plant for someone that hasn’t been to one in 30 or 40 years.

Well, the nature of what I used to do was, you know, have to learn about something and then spit it out. I recall doing some programs about adjusting doors. That was a big deal. These doors had a knife edge on them that actually made the seal. It was a metal on metal seal. And if there was some coke particle or something that screwed up the knife edge, you could have a leak in the door. And so that became a source of flames or smoke coming out so adjusting those doors was a process. There were all these little screws around the perimeter of this knife edge. And so if you get one too high, you’re going to create a gap next to it. So it’s kind of a ‘whack a mole’ thing. You have to go around and get them all on the same level, that was an interesting process. They always had extra doors in the area, so that when the door was leaking, they would move it off and put in a fresh door.

At seven or eight thousand pounds a piece.

Yeah, the stuff was enormous. In terms of the respirators they tend to be just like today, people don’t wear their masks, you know? Then they would pull off the respirator because they were very uncomfortable, especially in the summertime, and they were bulky. And so, they were really concerned about safety. In the tape you found, you’ll notice there’s a break, “your supervisor has some things to talk about”. Almost all the things that I did for them had that kind of a break. The purpose was to have them develop a rapport with the supervisor and discuss what they saw. So the supervisor could express concern and underscore the message. And in some cases, relay anecdotes of accidents that happened.

So you wrote that script yourself? I mean, did they give you something and say “you need to pull from this”, or did they just walk around and let you ask questions, take notes, and then…

They showed me how it works, I remember being there and just taking notes, and then there were iterations where they would look at it and make sure it makes sense. The thing is I actually started the business when I was still in college, and then I just got out. And so it was Interlake and ComEd a lot. A lot of stuff for ComEd. And that continued on for a long time. But Interlake was a kind of a big thing, because I think I charged them like $8000 for a series of programs.

That’s a lot of money even now. My God, triple that now.

That really helped start my business, you know? So It was a big deal.

Wow. Critical client.

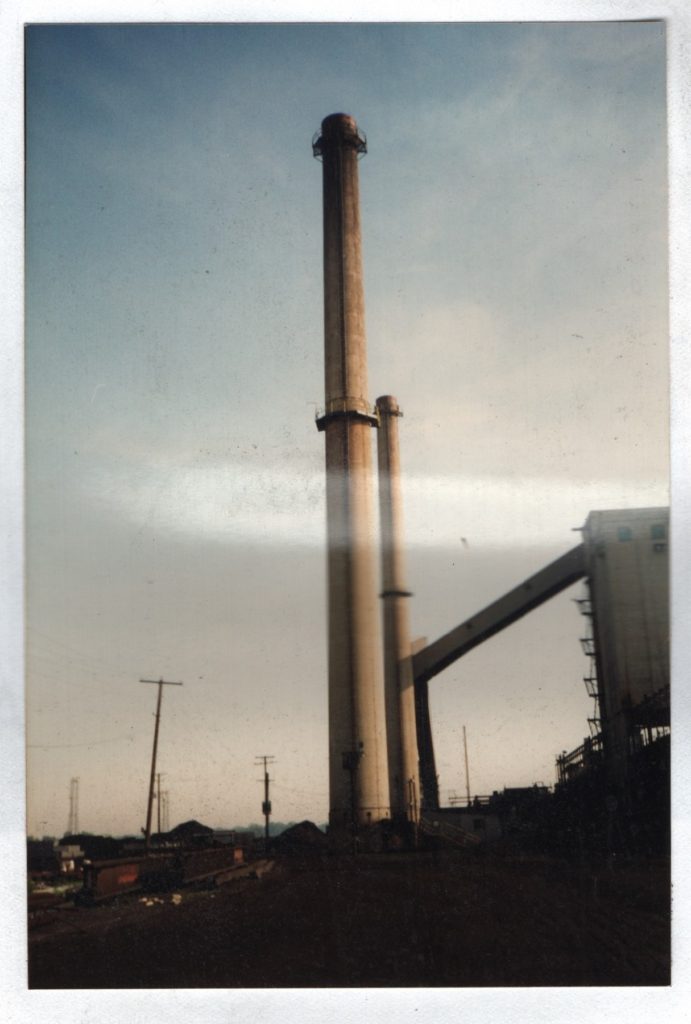

My one interesting memory has nothing to do with making coke. I was standing on the pusher side of the oven one day, just like talking with people, and there was rain coming in, and all of a sudden a lightning bolt came and hit one of those smokestacks. Iit was so fast and so loud. To this day. I remember that.

That’s got to be intense. Those are 250’ high. So I don’t know if I’ve ever been 250’ away from a lightning strike in my life. Probably not. You were.

It was pretty intense.

Yeah, that’s really, really close.

It was a very interesting place, you know? When they would quench the coke the steam would escape over the south side for miles and miles.

Do you know, off the top of your head approximately how many quenches they did a day, how many ovens would get pushed every day?

Well, I guess I think it’s roughly somewhere in the vicinity of a 15-16 hour cycle.

Correct, so it’s about 100. I’ve never had the privilege of seeing a quench in real life, you have. It’s an amazing, just mammoth event. So imagine the people that live in that area. They don’t see that once or twice a day, it’s 100 times a day, seven days a week. Christmas, Thanksgiving. You can’t turn the batteries off. You can’t take a day off. Every single day 100 times a day. Imagine that.

Oh, that’s crazy. Well, thanks for talking to me today. If you have any other questions offhand, don’t hesitate to send me an email.

I won’t. Thank you. Have a good night.